Tooth and Nail, Pt. 1: Battle over legality of dental therapists continuesREPOSTED FROM KTUU: Tuesday, May 9, 2006 - by Rhonda McBrideView the Video

Anchorage, Alaska - America’s first dental therapists are trained in New Zealand to help save teeth in rural Alaska, where the rate of tooth decay is twice the national average. Today they’re fighting a lawsuit from the American Dental Association.

Alaska’s dental therapists say they felt right at home in New Zealand. It’s a land a lot like Alaska -- rugged and remote.

Toksook Bay, a village on the Bering Sea, is one of the first communities in the United States to have a dental therapist. Lillian McGilton spent two years in New Zealand learning to do what people here need the most: basic dentistry. Yet the American Dental Association is suing, to keep her and other therapists from practicing.

“They don’t know me, they have not been to Otago University and, a lot of them just go on what they hear, and a lot of that information just is not accurate,” said McGilton.

According to the American Dental Association, Alaska is the only state that allows this type of dental care. It is not the only one fighting tooth and nail; the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium is biting back.

The debate has spilled into the headlines, letters to the editor, newsletters and television ads. Both sides have spent tens of thousands of dollars to win in the court of public opinion. One of the few things they agree on is that this money won’t cure a single toothache.

Now the battleground has moved outside Alaska. The controversy made a splash at a national dental conference in Little Rock, Arkansas. It’s hard to imagine why dentists from all over the country would even care about Alaska’s dental therapy program, but in Little Rock, a piece of the puzzle is revealed.

“We owe a great deal to these intrepid young Alaskans for what they have done,” said David Nash, DMD, University of Kentucky.

Most of those in the audience are rooting for Alaska’s dental therapists. They work in public health dentistry, and the ADA’s lawsuit has raised their interest in the program.

Aurora Johnson, a dental therapist from Unalakleet, tells people what it’s like to work out of school woodshop turned into a makeshift dental clinic.

“The air, the cold air was just coming right through,” said Johnson.

Most of the people here have never met a dental therapist before, including the man leading the charge against them: Bob Brandjord, president of the ADA. Initially Brandjord wasn’t invited to sit on this panel -- not until the ADA agreed that nothing said here would be used in its lawsuit.

“This is the first time that anyone from the American Dental Association has heard a presentation about our program,” said Ron Nagel, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium.

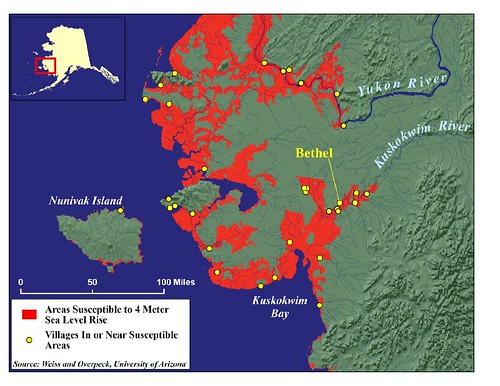

The presentation is often sort of a Bush Alaska 101. The geography is hard to grasp, let alone how dental therapists fit into the picture. That’s why Dr. Myron Allukian organized this panel. He’s the former dental director for the city of Boston and he has taught at Harvard University.

“To me, we’re one dental family and we should be working together,” said Allukian.

But when it comes to expanding the role of dental workers, Allukian is often at odds with the ADA.

“I’ve fought these battles over and over with organized dentistry,” said Allukian.

Allukian got the American Public Health Association to pass a resolution supporting Alaska’s dental therapists. It’s his way of pushing the ADA.

“Any time there’s a new concept, they have a very slow learning curve. And they oppose these new concepts. Then 10, 20 or 30 years later, they’ll say, ‘Gee that’s a good idea,’” Allukian said.

Allukian says this battle is similar to one the American Medical Association fought years ago to block nurse practitioners and physicians assistants.

“You go to the AMA now and say, ‘We’re gonna eliminate all nurse practitioners,’ they’d fight tooth and nail to keep the nurse practitioners, because they’ve been a great adjunct,” said Allukian.

“I think we have been portrayed basically unfairly in most of the debate and we are not stagnant, we are not stick-in-the-muds about trying to improve our delivery of dental care,” said Brandjord.

The ADA’s main objection is that dental therapists are allowed to do what are called irreversible procedures, like fill cavities, do tooth extractions and pulpotomies, a nerve treatment similar to a root canal.

“If we could resolve the issue about irreversible procedures, we would have no problem. We support everything else in the program,” said Brandjord (right).

But it’s a program the ADA knows little about.

“I think they should go to New Zealand. I think if they went to New Zealand, they’d see how dental therapists work,” said Lyndie Foster Page, New Zealand dentist.

Page helped to train some of Alaska’s dental therapists, including Aurora Johnson.

“I just wanna seem them go and make a difference. Get out there and maybe just show some of the Americans that it can work, like we have in New Zealand,” said Page (left).

Dental therapy has a track record that goes back to World War I. They were called dental nurses back then and traveled New Zealand on horseback. Today they’re in every public school.

“New Zealand is not a very litigious country, but still there are complaints about dentists. There are complaints about doctors. So if there were serious complaints about dental therapists in the past, these would have been acted on,” said Page.

“Organized dentistry in America is very ethnocentric. I’ll put it that way. Our profession has certain attitudes and values. And now we think the time has come to be sure that we have evidence of what dental therapy is doing around the world,” said Nash.

Nash is heading up an international study on dental therapists, to find out how therapists might help millions of Americans who can't afford treatment.

“I think for the people of the United States, the future of the oral health of their children is at stake,” said Nash.

So in a handful of Alaska villages, a national experiment is taking place. It’s one that the American Dental Association says puts people at risk, and one that national public health experts say is full of promise.